From the Spring 2010 issue of Scrubs

From the Spring 2010 issue of Scrubs

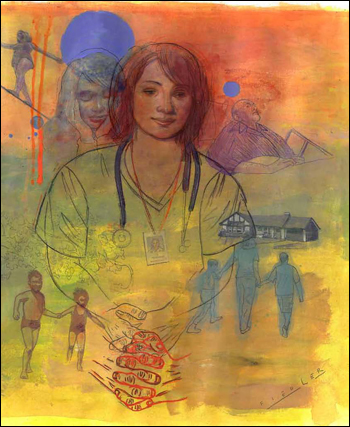

“I don’t know how you do it.” Patients have been saying this to me a lot lately, and it has made me wonder: How do I do the work I do? How do any of us nurses do our jobs? And then how do we go home and live normal lives away from the suffering and dying we face every day? These are questions we need to answer if we are to continue keeping drive and desire intact, and burnout at bay.

The short answer is that nurses either make peace with the emotional demands of the job or find a different one. Mostly I have made my peace with it, but some days are harder than others, and those are the days when the “how” of coping really matters. I’ve had a few of those days lately, and they’ve made me think about what I do to keep the sadness of the floor, and the enervating work that regularly confronts death, from taking over my life.

A few months ago, a patient—a woman roughly my age, 44—was actively dying. When she was admitted with a diagnosis of leukemia a year before, she was energetic and bubbly. She had been a hairstylist, and once she started to lose her hair, she borrowed clippers to shave her head. When a rounding attending told her that being bald suited her, that she had a “nice-shaped head,” my patient thought this was hilarious, and her strong laugh was hard to resist.

Now, close to death and doped up on morphine, she could not chat with, listen to or even notice the people around her. Her husband and I talked, though. In the hallway outside her room, he looked at me, shaking his head. “I don’t know how you do it,” he said, imagining the toll the job took on me.

Two years ago, when I first started as an oncology nurse, I would pretend an emotional immunity in these conversations, a placid resilience, that I did not actually feel. Over time I admitted to myself that demurring was really only a way of lying about how the job taxes me. So this time I looked at my patient’s husband and thought about an honest response. “Well,” I said, “I have three kids, and they really do rejuvenate me.” The husband looked at me, surprised, and then nodded his head.

An explanation, however, is not an action—and to stay sane in this job, you have to act. As soon as I could, I called my husband. “Hey Arthur,” I said, “how about you pick me up when I get off work and we take the kids to Max & Erma’s?”

My son Conrad, who’s 13, and Miranda and Sophia, 10-year-old twins, really like the local Pittsburgh chain restaurant. But they know it’s not a place I would ordinarily choose, so they asked me, with that unselfconscious directness children have, why I suggested going. Once again, I thought about my answer. I often try to soften or even hide the hardest truths about my job. This time, though, the truth seemed like the best idea.

“A patient I like very much is dying from cancer and I was feeling sad about work,” I told them. “Seeing you guys makes me feel better, so I wanted us to go to a restaurant you really like.” All three of them sat silently for a few seconds, and then, like my patient’s husband, they all nodded.

The restaurant’s hum returned, along with the kids’ chatter. Miranda described the fifth grader who spent too long in the bathroom, Conrad bemoaned the librarian who could not control her class and Sophia complained about homework. The conversation was like a salve on my soul.