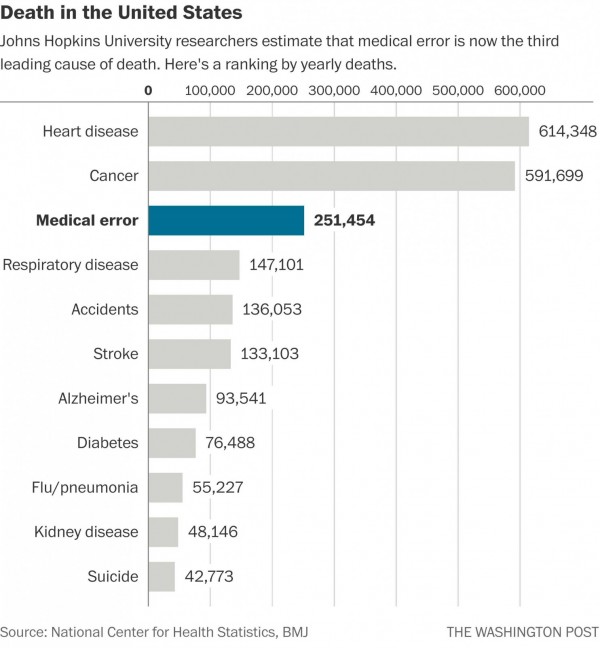

Earlier this year, Johns Hopkins Medicine released a study that made many people think twice about their fates when being admitted to a hospital for care. In it, researchers suggested medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the United States.

Leading causes of death identified in recent Johns Hopkins Medicine stud

They urged the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to change the way they collect annual vital health statistics, adding “medical error” to the list of the most common causes of death.

Why?

When people die in hospitals, their death certificates cite cardiac arrest, congestive heart failure, or any number of clinical causes of death. What’s missing? The medical missteps, communication breakdowns, and fatigue-induced neglect—conditions that can result from understaffed nursing units, for example.

A Chicago Tribune investigation revealed a host of contributing risk factors associated with nurse staffing: mandatory overtime, 16-hour shifts, and improper care provided by unlicensed, unregulated nurse aides hired to fill temporary staffing gaps.

No one goes into nursing to kill people—quite the opposite. But the reality is that no matter how hard overwhelmed nurses work to provide the best possible patient care, conditions in many hospitals today often make it difficult for nurses to keep patients alive. Having enough staff is of course a critical piece of the puzzle, but so is being able to effectively and efficiently leverage the staff you do have–and we find that the impact of nurse managers and schedulers having a difficult time filling open shifts isn’t discussed enough.

What’s happening?

Theresa Brown, nurse and author of The Shift, describes the reality in an interview with NPR:

“There’s a sense that you can stretch a nurse just like an elastic band and sort of go, ‘Well, someone called off today.’ That means a nurse calls in and says that she’s sick or her car broke down or he won’t be there, and sometimes we’re able to get someone onto the floor to take that person’s place, but often we’re not. Or an aide might not be able to show up for whatever reason, and then the assumption is just, ‘Well, the nurses will just do all the work that the aide would’ve done,’ and the problem is that people do not stretch like rubber bands, and even rubber bands will break if you stretch them too far.”

Brown’s experience isn’t unique. NurseGrid’s VP of Nursing, Zach Smith, has his own personal anecdotes:

“Suppose I have a patient with MRSA; it’s resistant to some of our strongest medications and spreads rampantly when immune systems are down. As a nurse, I’d have to put on a gown and gloves just to enter this room and then wash my hands extensively afterwards. It’s a very time-consuming process just to touch such a patient. And when we’re overworked, we take short cuts we know we shouldn’t take—because there’s simply no other option. There just aren’t enough nurses to take consistently safe care of all these patients when a unit is short-staffed for a shift.”

Nurse managers want to prevent their nurses from snapping like worn-out rubber bands, but it’s tough when they’re trying to fill open shifts—on the fly or ahead of time—using inefficient processes like phone trees and mass texts or emails.

As a result, sometimes the staffing holes don’t get filled and nurses on duty have to pick up the slack, sacrificing sleep. And nurse fatigue is one factor that threatens patient safety. Studies show that lack of sleep increases the risk of making errors, and that when a nurse is awake for 19 hours, it’s the same as having a blood alcohol content of 0.05%.

Other times, nurse managers have to cover staffing gaps with expensive agency staff. And that costs the hospital more money.

What’s the answer? Nurses, nurse managers, and nurse advocates we work with agree on some ideas:

- Make sure you have access to the right data: If it’s easy to understand nurse availability and overtime implications when you’re looking to fill an open shift, whether you need someone tonight or ahead of time, you can target requests to the right staff members rather than to everyone.

- Communicate staffing needs more effectively: Managers and schedulers should have an easy way to communicate open shift requests to the staff candidates they identify, ideally with relevant mobile messages or notifications that exist outside the steady stream of department emails and texts that many nurses can’t keep up with. That way, staff members feel less overwhelmed and more likely to respond.

- Give nurses easy access to and more control over their schedules right on their phones: When it’s easy for nurses to see their schedule at a glance and initiate and get responses to schedule change requests when needed, they’re more likely to pick up open shifts. In a recent survey of our NurseGrid Mobile users, 85% of over 2500 nurse respondents said they would be more likely to pick up extra shifts if they came through the NurseGrid app.

Tell us about your experience with being short staffed on a shift. How often does it happen? Does it compromise your ability to ensure patient safety? What are your ideas to correct the problem? And to learn more about how our tools for managers and schedulers can help you ensure a properly staffed unit, visit us online or email us at he***@nu*******.com.