From the Winter 2010 issue of Scrubs

From the Winter 2010 issue of Scrubs

Myths and misconceptions abound in every profession, and nursing is no exception. Sometimes these myths come from colleagues, sometimes from people outside the profession—either way, they don’t serve us well. So, next time you hear a stereotype you know is nonsense, use your know-how to clarify, inform and enlighten.

Myth: “Real” nurses work in hospitals.

Fact: More than half of all nurses work in hospitals, but that doesn’t make them more “real” than the rest of us. I used to work in an emergency room, and I can tell you for certain that I have been as much a nurse since I left as I was in the hospital (I’ve done everything from conducting medical exams for insurance companies to preparing nurses to take their boards for an education company).

Yet, from the day I stepped out of the hospital into the world of nontraditional nursing, the questioning (“Why did you leave nursing?”) started. And it has never stopped. I always give the same answer, very calmly and very proudly: “I never left nursing. I’m still a healer, teacher and nurturer.” I have a very broad view of who a nurse is and what a nurse does.

While many of us wear scrubs, there are still nurses who wear uniforms, business clothes, even overalls. Being a nurse is about who you are, not about what your wear or where you work.

Myth: Patients like to be called by their first names. It’s just friendlier.

Fact: With all the available techno-communication—from email and IM to MySpace and YouTube—we’ve become an increasingly informal society, and sometimes we automatically address people by their first names. Many patients are more comfortable with formality in the health care setting, and the use of surnames and titles helps maintain the professional relationship. Plus, there are many people, especially older individuals, who consider it disrespectful to be addressed by their first names.

The bottom line: Be sensitive to your patients’ preferences. It’s probably safest to start out with formal forms of address and progress from there.

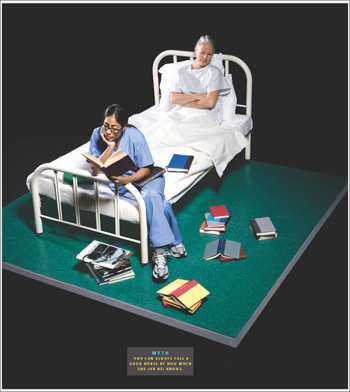

Myth: You can always tell a good nurse by how much she or he knows.

Fact: An excellent store of information and experience is essential in a nurse, no question about it. But a deep sense of empathy and compassion are equally important. A nursing instructor at a community college told me that she always explains to new grads, “Patients don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.”

Myth: Apart from the language issue, most foreign-trained nurses find that working in an American hospital is not much different from working in their home country.

Fact: Foreign-trained nurses now account for about five percent of the total United States nursing workforce, and are an intrinsic part of our health care system. Thank goodness, because there are some parts of our country that are suffering from a nursing shortage. Most foreign-trained nurses, despite their high skill level and excellent training, still have to sort out a host of cultural issues and professional expectations that they often hadn’t expected.

Nurses from the Philippines, for example, who make up nearly half the foreign-trained nurses, usually find they have much more responsibility here. They also have to be more independent and use more critical thinking skills. Why? Because in the Philippines, most hospitals are teaching hospitals, and the residents and medical students do most of the procedures. When they get to the United States, nurses find, for example, that they’re required not only to start IVs, but are also supposed to interact with doctors and patients’ families, even if they’re not the charge nurse; additionally, they’re responsible for discharge planning and case management. Add to all this a brand new language, and you can really see what foreign-trained nurses are up against.