From the Fall 2010 issue of Scrubs

From the Fall 2010 issue of Scrubs

I never wanted to be a nurse. When other 10-year-old girls were reading Cherry Ames, Student Nurse, I was pretending my Schwinn was a bay stallion and together we were galloping down Sylvandell Drive in Pittsburgh, always under the gray cloud of steel-mill smog that hung in the sky. When I was 12, most of my friends donned candy stripers’ uniforms while I signed up for Saturday art classes at the local museum. After high school graduation, my candy striper friends debated the size, shape and overall appearance of nursing caps—the criteria for deciding which nursing schools they’d attend—and I went off to Gettysburg College, where I wrote poems, wore black net stockings, played guitar and grew my hair down to the middle of my back. The thought of giving someone a bedpan gave me the creeps. But life has a way of sending us where we never thought we’d go.

Move forward several years: I’m married with a baby, and my husband and I aren’t meeting the monthly rent. His cousin, a nurse’s aide, suggests that I become one, too: on-the-job training, flexible hours and, best of all, decent pay. My very first night, I was introduced to the world of nursing in ways I’d never expected. I walked into a room to take an elderly man’s vital signs and found him cold and dead in bed. For several minutes I sat watching him, awed at the sight of this human being whose soul had recently departed, leaving his body a fragile husk. I held the old man’s hand, suddenly filled with sorrow that he had died alone. I touched his yellowed fingernails. I leaned close and memorized his face. Only then did I tell the nurse.

Later that same night, a patient’s husband called me an “angel of mercy,” and a woman waiting for the results of her biopsy told me how afraid she was. While I gave her a back rub, she wept. Afterward, she caught my hand and told me how grateful she was for my care.

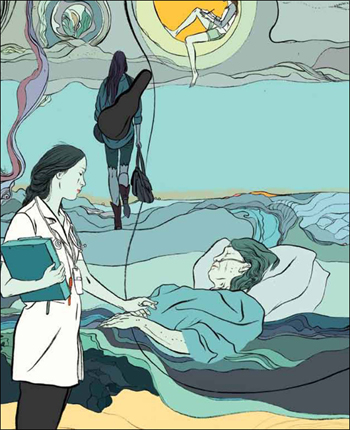

The hospital, I quickly learned, was a different world, one where people suffered and died. In the hospital, there was an undercurrent of mystery, sensuality, spirituality—here, love and caring were primal, like the love between a mother and a child, with all of that relationship’s fears, longings, difficulties and joys. When I gave my weeping patient a back rub, my hands soothing her skin, I felt the same difficult-to-define selflessness I felt caring for my baby girl.

Little by little, I began to like my job. I understood that in the hospital, during all those intimate and critical moments between nurse and patient, the caregiver becomes the transparent giver, and the patient is the very real receiver. Often sick or dying, a patient, like an infant, is helpless to do anything but exist in the moment. As a nurse’s aide, I found great joy and great peace in the smallest but most important interactions: offering a cold glass of water to a thirsty patient; holding a lonely old woman’s hand; listening to a man talk of his life, almost over. When I returned home at the end of my shift, everything was more precious. Everything reminded me that this other world—the suffering hospital—existed 24 hours a day. If I woke at 3 a.m., I knew that while I nursed my baby, somewhere a nurse might be feeding a patient or giving a patient pain medication or saving a patient’s life. When I walked through the hospital doors in my squishy shoes and my neat blue uniform, not knowing what I would find, my heart opened, like a hand.

Two Worlds

Still, my two lives were very separate. At home I let my long hair fly loose, I wrote poems about my growing daughter and soon about my new son, and I still played my guitar, not the folk songs of my college days, but lullabies. In the hospital, I became someone else—a braver someone, a more humble someone. For some reason, it seemed that those two worlds wouldn’t or shouldn’t become one.

Move forward again: My husband and I aren’t getting along, perhaps the strain of so little money and so much work, the tight corners of our apartment. We divorce. A position opens up in the OR for a surgical tech, which means more on-the-job training and a better salary, so I sign on. A year later, masked and gowned, I’m slapping instruments into surgeons’ hands.

In the OR, just as I was on the floors, I’m surrounded by human misery and human transcendence. A drunk man bleeds out at midnight as the surgeons and I frantically race to remove his lacerated spleen; patients, almost anesthetized, stare into my eyes, the only part of me they can see, and I hold their gaze. In the OR, colors and sights and sounds swirl around me. The colors of the opened body are lovely—the glassy pink intestine, the deep red of muscle, the pearly white of tendon and bone. At home, my poems become more sensual, more aware of sounds and smells, the smallest nuances. Yet still, my two worlds revolve around one another, spinning in tandem, like electrons, but they never collide.

The surgeons tell me, “You’re good; you should become a registered nurse.” I take their advice and go to a local community college to do just that. I become friends with one of the other students and, to survive financially, she and her son move into my four-room apartment. We both work part-time, different days and shifts, watching each other’s children and then, exhausted, we study until 3 a.m. By the time we graduate, my friend and I can run a busy floor, care for ventilator patients, give injections, pass meds and resuscitate a coding patient with our eyes closed. I step right into a night job in Intensive Care, and she becomes a psych nurse in a tough rehab unit. Our days of financial scraping behind us at last, my kids and I have our apartment back, and my blossoming paycheck fills the refrigerator and buys everyone new shoes.

My boyfriend and I get married. We move to a house, and I take another ICU job in a bigger hospital. Within a year, I’m promoted to head nurse on the brand-new 20-bed oncology unit. I witness the most intense suffering and the most intense caring imaginable. I was a good nurse before; on this ward, I become a real nurse. Then one day, one of my favorite patients dies unexpectedly. I sit dazed at the nurses’ station. This woman was my age, and her kids were the same ages as my kids. Her death, more than any other that I’d witnessed, shook me to my soul. All my years in caregiving, everything that I’d seen and done, all the patients who lived or died—all those memories and moments seemed to overwhelm me. I almost quit nursing, asking myself, Why bother? How can what I do possibly make any difference? Again and again, I’d run head-on into the cold, stone wall of suffering and death, but this time I was unable to shake off my grief and simply go on. I couldn’t, didn’t, heal my patient. Now, how would I heal myself?